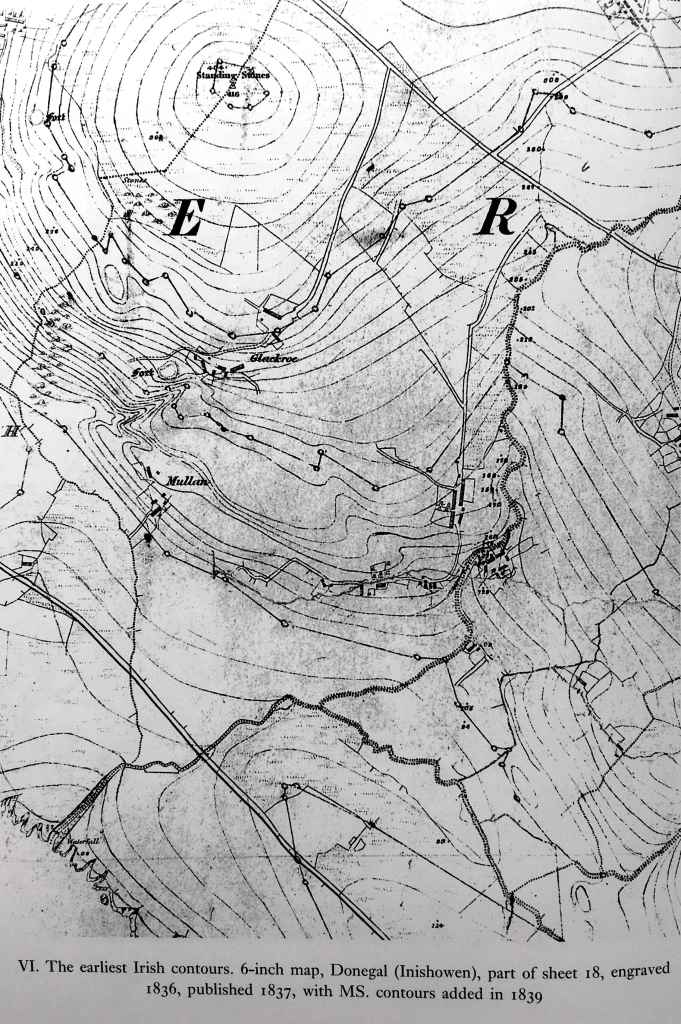

My blog began with a tale of the contouring of Schiehallion in Scotland. It is a mountain that has proved itself very attractive on many occasions. Another magnificent peak is Slieve Sneacht in Ireland, and both are associated with momentous mapping innovations that have anniversaries this year.

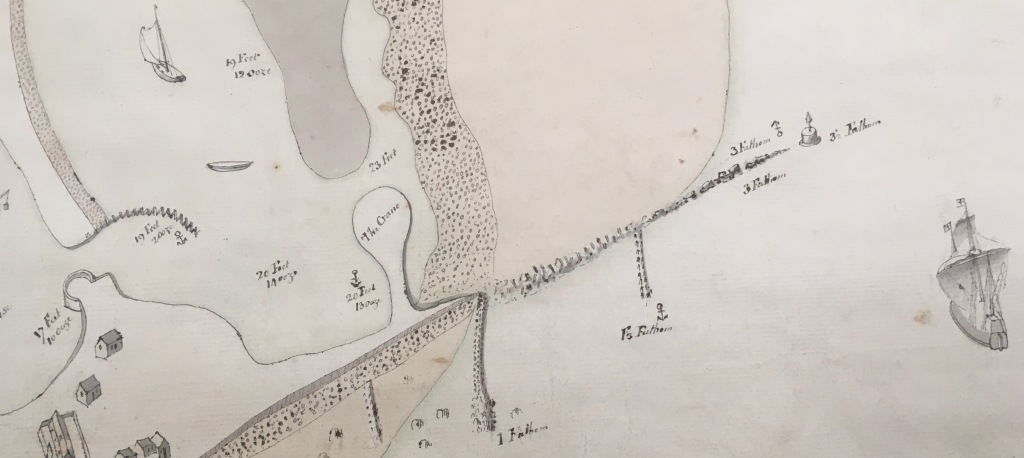

2024 marks 250years since astronomer royal, Nevil Maskelyne, began his “astronomical experiment of the attraction of a mountain”. His task was not to devise a system for rating beauty, rather to oversee an experiment to gauge the weight of the earth. From observatories erected high up on Schiehallion’s north and south facing flanks, Maskelyne charted the position of stars. Having ascertained their heavenly positions, he used these as a measure for minute deflections from vertical in a plumbline, thus assessing the mountain’s mass through horizontal gravitational force. My knowledge of how the experiment worked is limited because what had piqued my interest was a by-product of it. My focus was the mathematician, Charles Hutton. He had been tasked with mapping the volume of the mountain, and aided by the meticulous measurements of surveyors, he derived a novel solution for it. He wrote of “connecting together … all the points [spot heights] which were of the same relative altitude.” His contour lines were likely the first drawn on a practical terrestrial map. (The anniversary of the creation of his map will be a few years beyond the beginning of the experiment.)

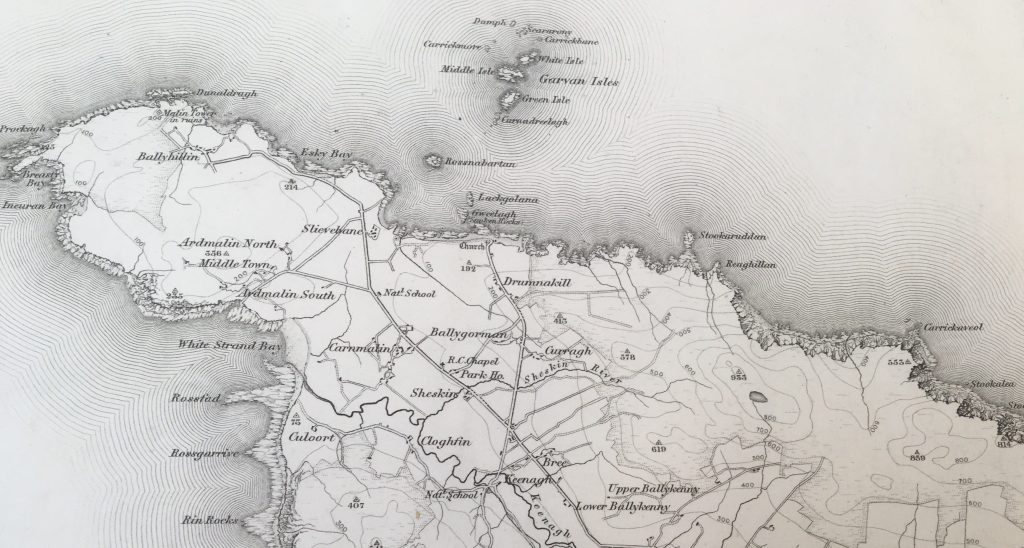

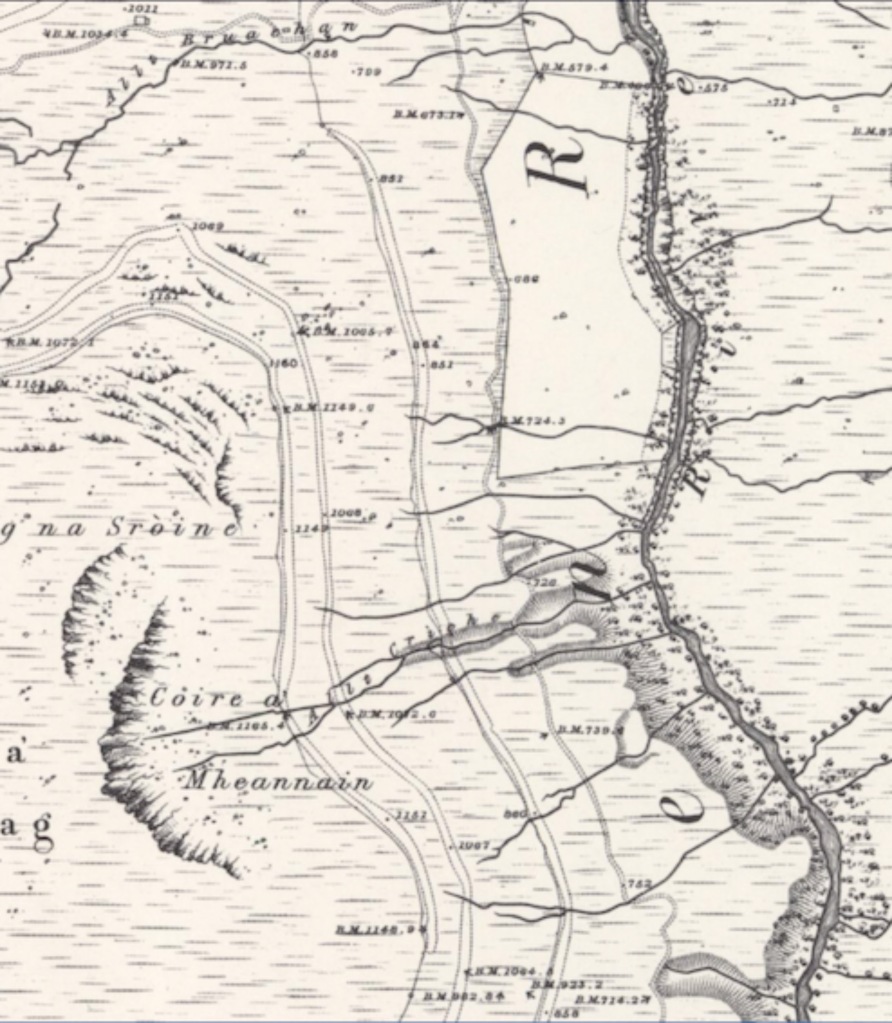

The other attractive mountain with an anniversary pending is Slieve Sneacht on the Inishowen Peninsula in Donegal, Ireland. Two hundred years ago, the Ordnance Survey shifted the focus of their mapping activities from England to Ireland. If you look at their printed sheet numbers, no. 1 – in any series of Ireland – begins with Malin Head at the tip of the Peninsula. It is as though the upper lefthand corner of Ireland becomes the ‘once upon a time’ of a story.

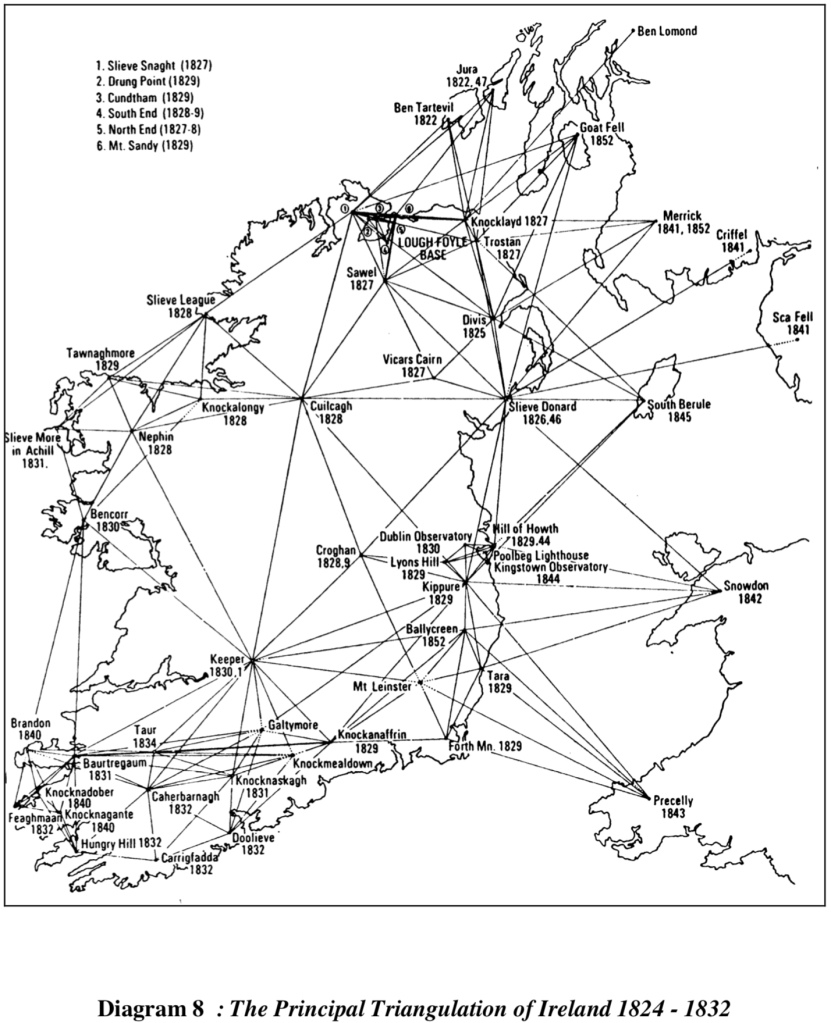

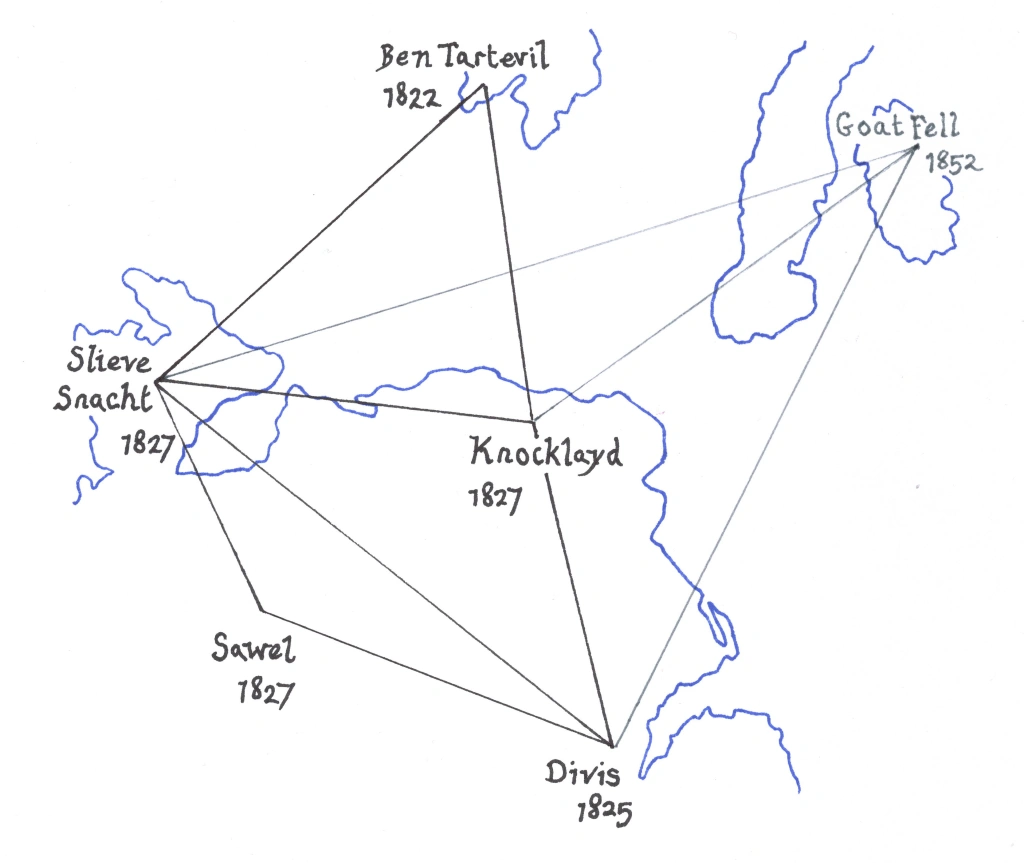

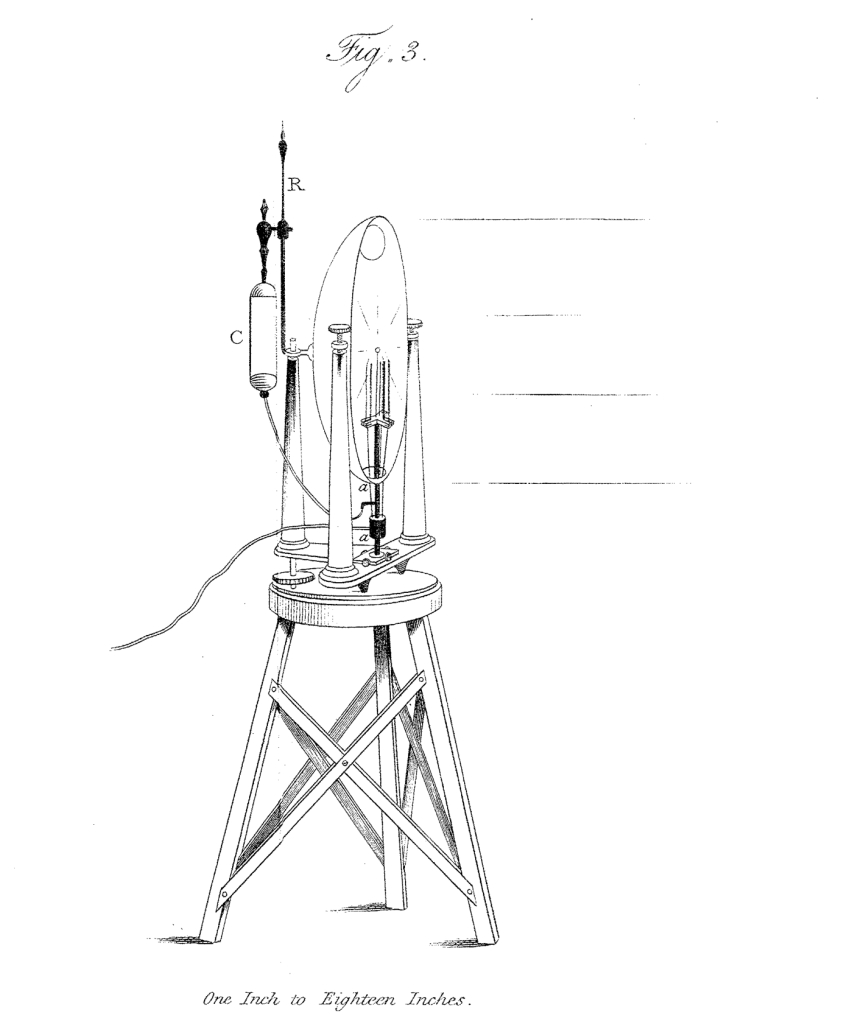

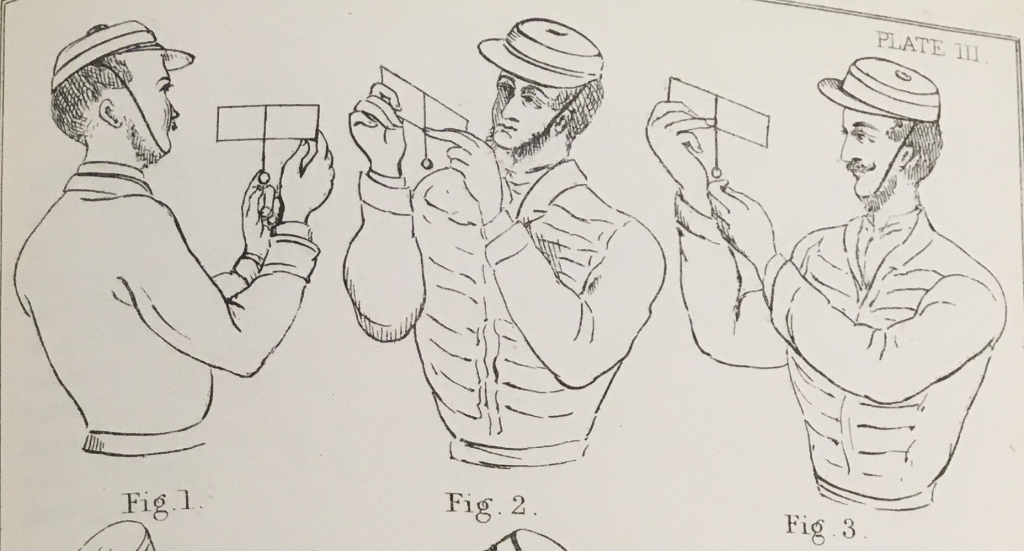

The OS’s initial surveying activities were also based there abouts: a baseline was measured along Lough Foyle, east of Slieve Sneacht, whose summit played an important role (along with Divis and Knocklayd) during the trigonometrical survey of the country. These surveys were made by erecting camps on mountaintops so that signals could be sent from one to the next. The process worked well in clear weather conditions, but just as for Maskelyne on Schiehallion half a century before, months could be spent in wind battered bothies, cloaked in inveterate haze and fogginess (as Colby described it). To speed up the triangulation the OS needed a signalling light stronger than their Argand lamps. In a paper “On the Means of Facilitating the Observation of Distant Stations…” Thomas Drummond described such a light, and on the November 9th, 1825, the mist piercing beam from his new invention was received 66miles away on Divis. Reckoned to be 37 times brighter than Argand, Drummond had invented Limelight.

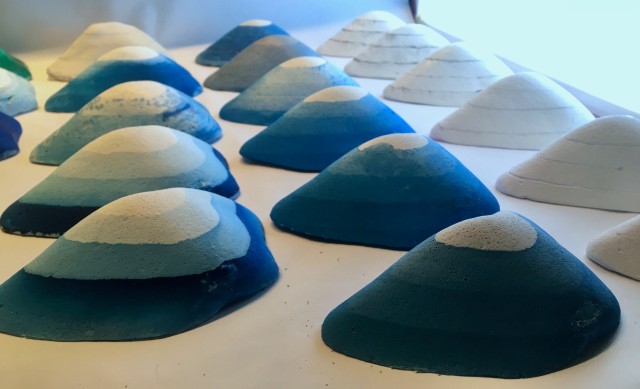

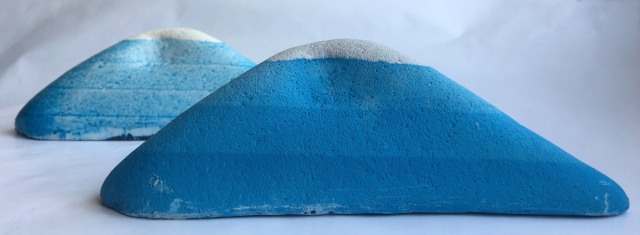

As with Schiehallion, the anniversaries connected with Slieve Sneacht have multiple dates worth celebrating. But we are beginning this summer with a month-long project at Artlink on the Inishowen Peninsula.

I get stuck on hills. I spend hours poring over mountains on their paper mates; fingers track, stub and circle notable features as I try to transform their graphic qualities into

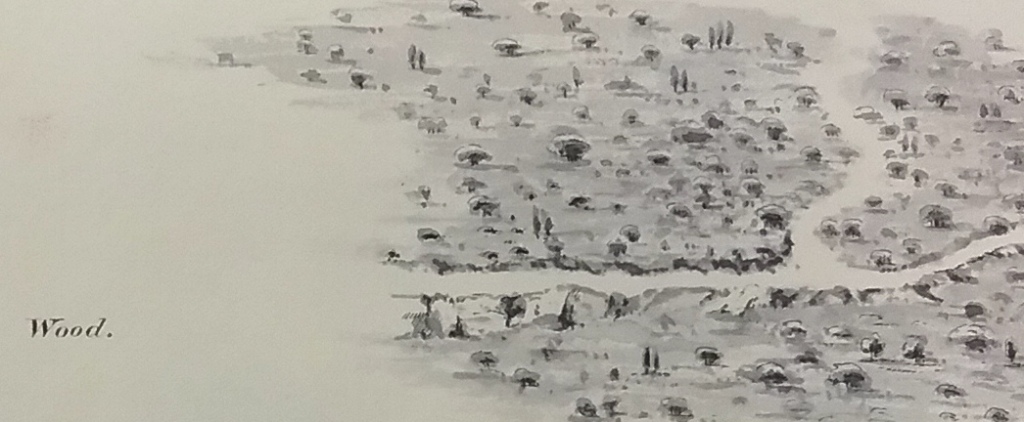

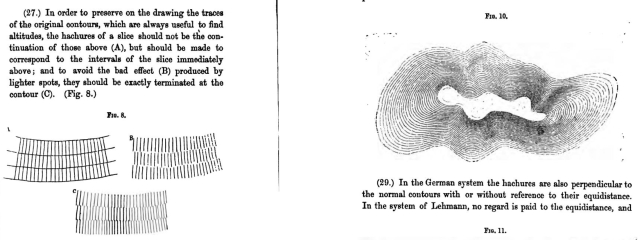

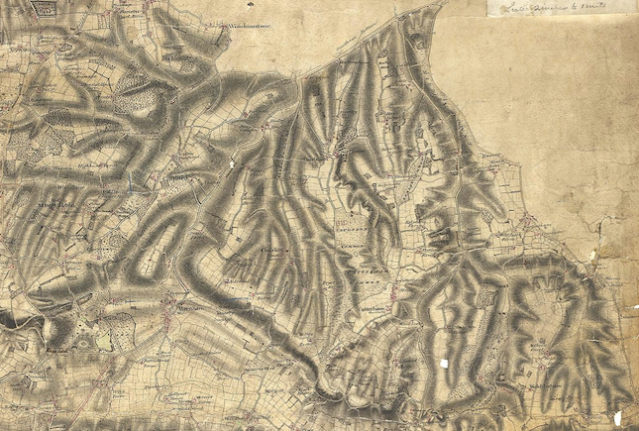

I get stuck on hills. I spend hours poring over mountains on their paper mates; fingers track, stub and circle notable features as I try to transform their graphic qualities into  Draughtsmen at work in the early years of the Ordnance Survey reached for myriad

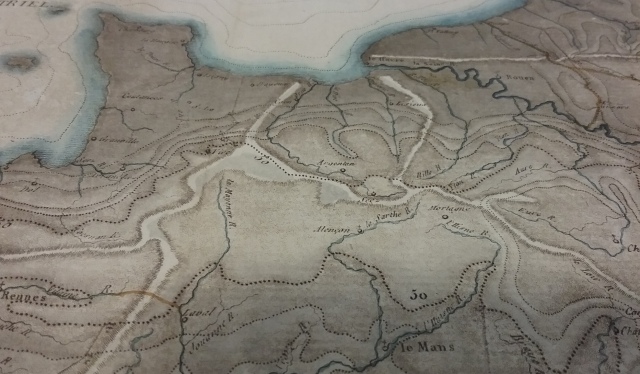

Draughtsmen at work in the early years of the Ordnance Survey reached for myriad  Dupain-Triel was a millipede man. In 1782 he created a map of the ‘main chains’ of mountains (millipedes), and principle courses of the rivers of France. Nine years later he eschewed the millipede to produce one of the earliest printed contour maps. It is the same size and outline of France as the earlier map, only this time the ‘different height of its plains’ is foregrounded and the rivers are not nearly as eye catching. Things get strange on a third map printed in 1802: same size again, same outline; only this one is overprinted so that millipedes and dotted contours collide. Like the stopped clock that is correct twice a day, rarely do these two evocations of the mountain chains accord. We desire maps to tell us the truth, but here Dupain-Triel cruelly dashes expectations; all over the map, millipede chains traverse contours lines in a confusion of impossible highs and lows worthy of an Escher.

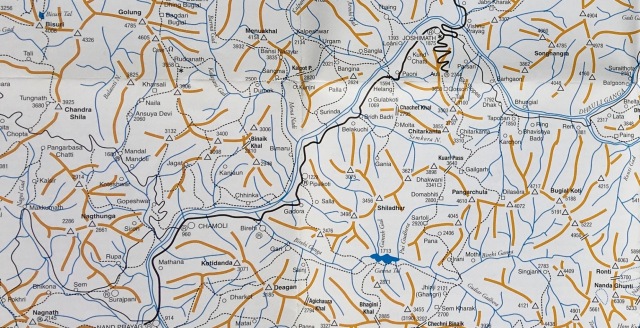

Dupain-Triel was a millipede man. In 1782 he created a map of the ‘main chains’ of mountains (millipedes), and principle courses of the rivers of France. Nine years later he eschewed the millipede to produce one of the earliest printed contour maps. It is the same size and outline of France as the earlier map, only this time the ‘different height of its plains’ is foregrounded and the rivers are not nearly as eye catching. Things get strange on a third map printed in 1802: same size again, same outline; only this one is overprinted so that millipedes and dotted contours collide. Like the stopped clock that is correct twice a day, rarely do these two evocations of the mountain chains accord. We desire maps to tell us the truth, but here Dupain-Triel cruelly dashes expectations; all over the map, millipede chains traverse contours lines in a confusion of impossible highs and lows worthy of an Escher. There is one final ‘map of chains’ that has won a place in my heart. Here the paper is strewn with orange stickmen who have joined hands or lost legs, their waists and shoulder joints marked by spot heighted triangles. Rivers systems snake between them in blue while black dotted paths follow their courses before – very occasionally – heading directly for an orange leg or arm, then courtesy of a pass marked by a little bridge symbol “=”, cut across the ridge to join the banks of a different river. I was enjoying looking at its refreshing brevity of style while on a visit to the studio of fabulous ‘mountain artist’

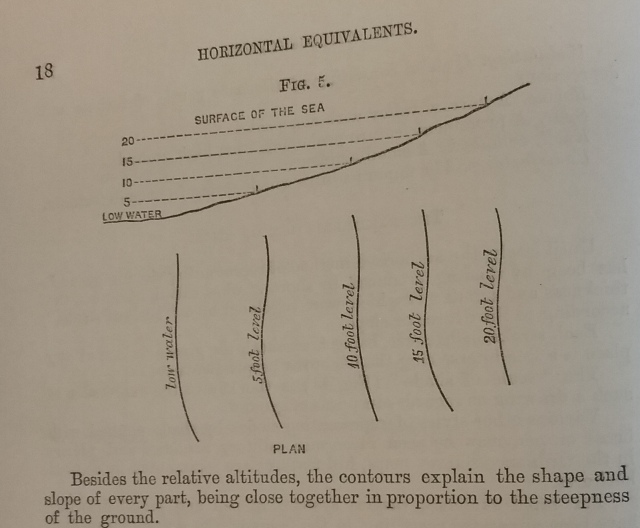

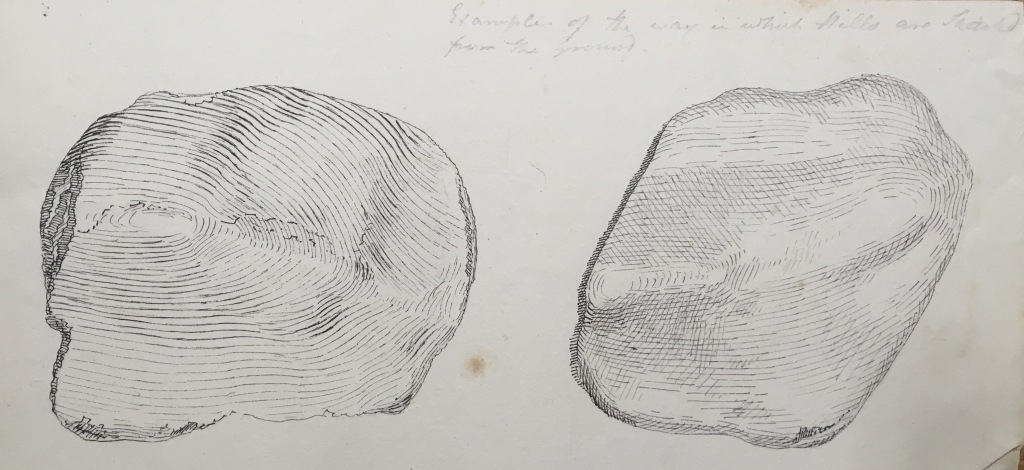

There is one final ‘map of chains’ that has won a place in my heart. Here the paper is strewn with orange stickmen who have joined hands or lost legs, their waists and shoulder joints marked by spot heighted triangles. Rivers systems snake between them in blue while black dotted paths follow their courses before – very occasionally – heading directly for an orange leg or arm, then courtesy of a pass marked by a little bridge symbol “=”, cut across the ridge to join the banks of a different river. I was enjoying looking at its refreshing brevity of style while on a visit to the studio of fabulous ‘mountain artist’  How do you explain what a contour line is? G. D. Burr’s advice was to “Procure a stone somewhat resembling a hill”

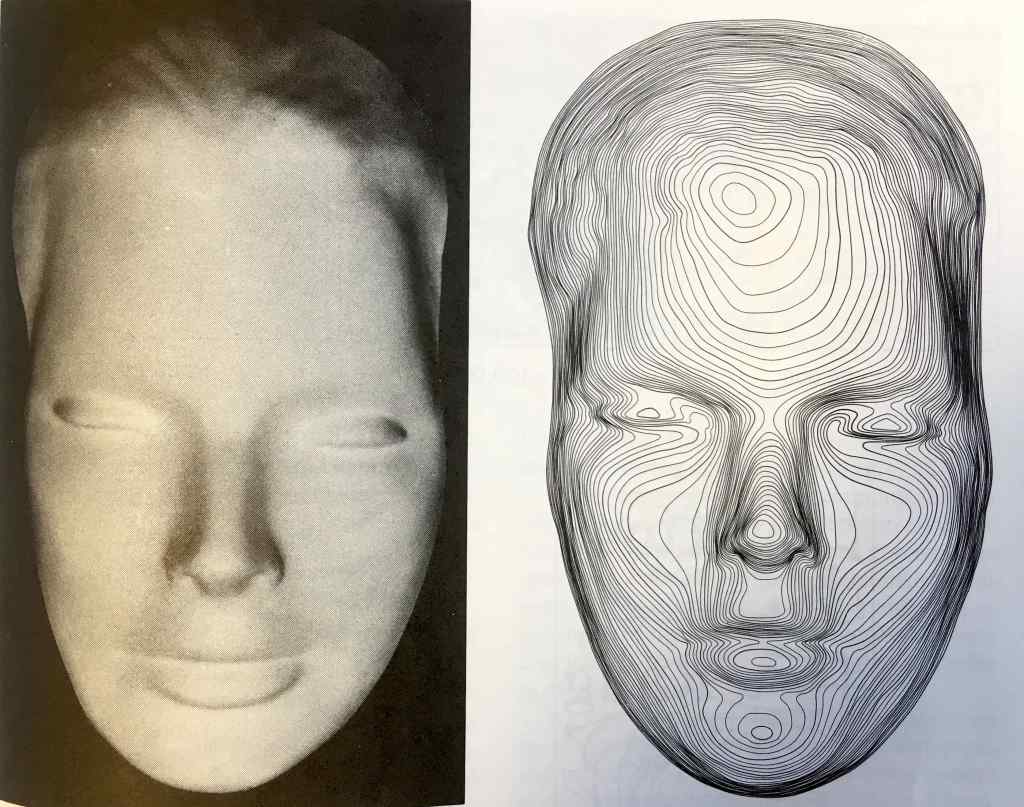

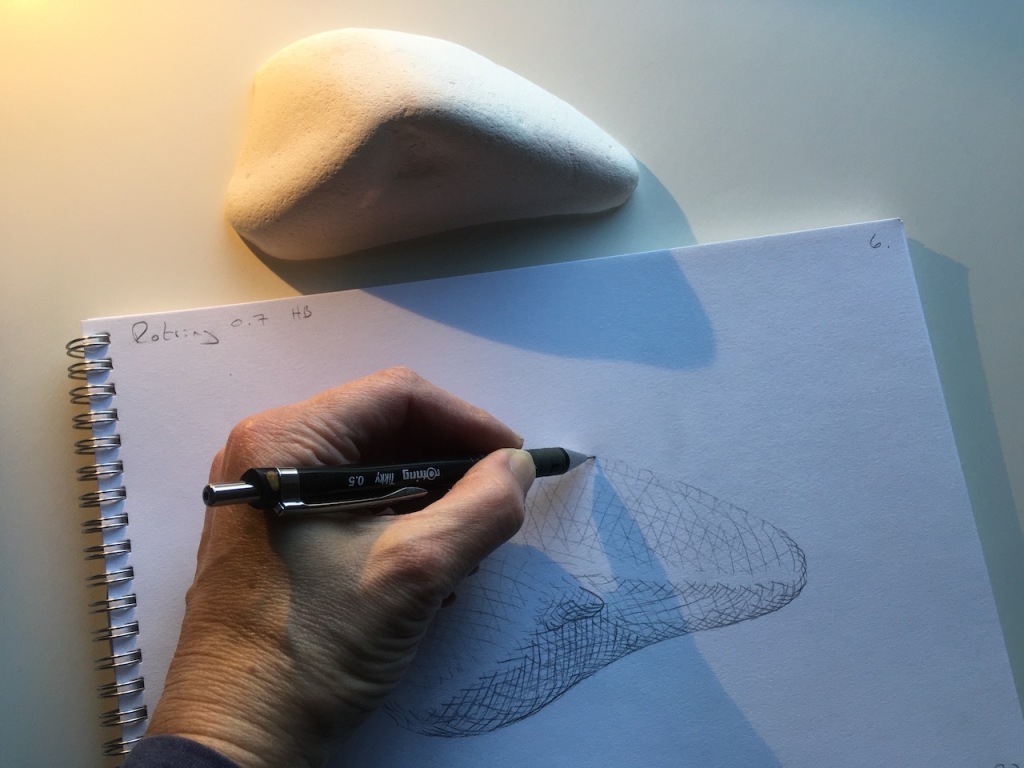

How do you explain what a contour line is? G. D. Burr’s advice was to “Procure a stone somewhat resembling a hill” Three years later Basil Jackson described “a very ingenious and striking”

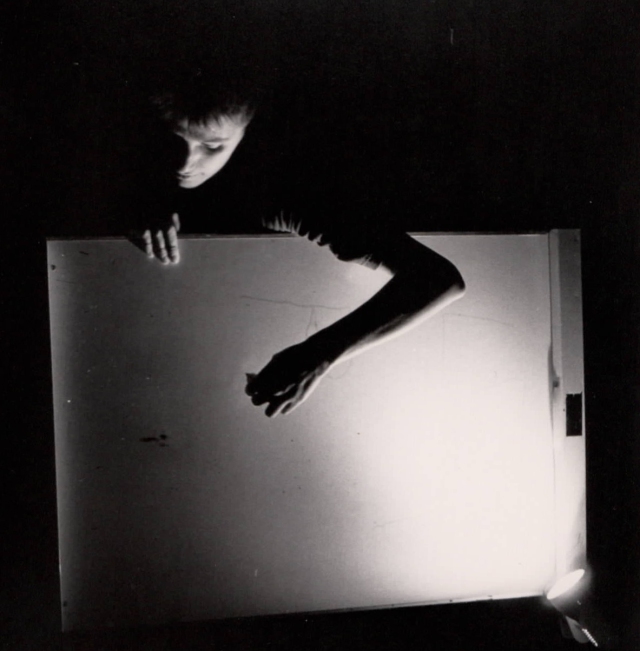

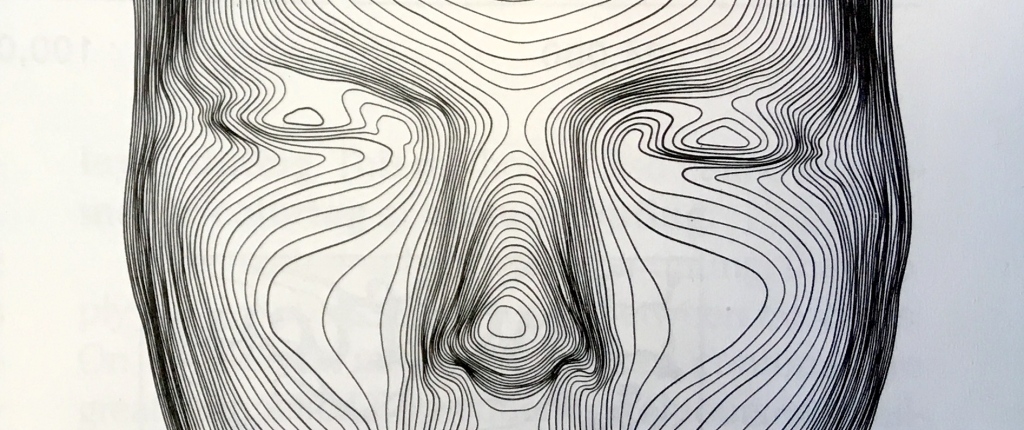

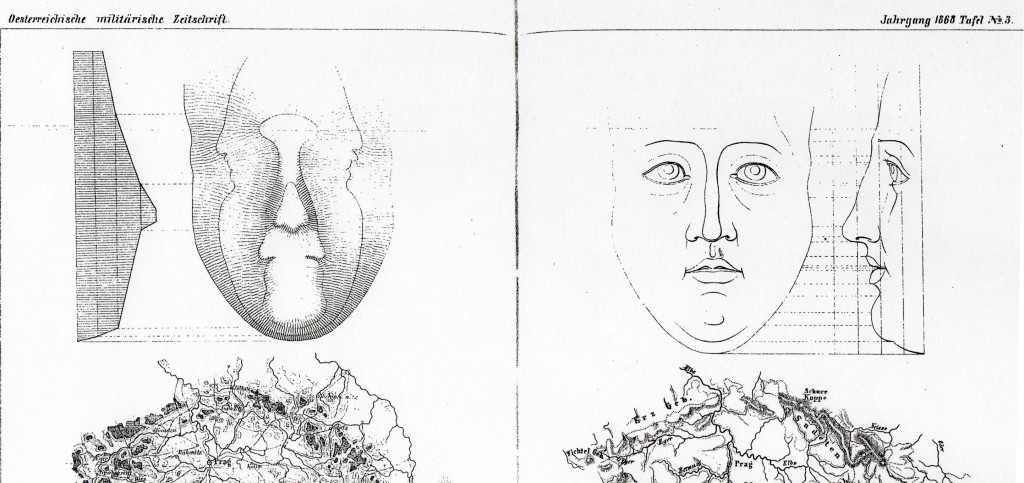

Three years later Basil Jackson described “a very ingenious and striking” except in Jackson’s version ink isn’t used, the water is clear and: “At every successive fall of the water, he [Burr] traced lines on the model, indicating the curves shown upon its surface by the successive lowering of the water.” I tried recreating this version too, but ‘tracing’ with a sharp point tended to nudge the model, and ink (and charcoal and graphite) smudged in the water. To draw a steady clean line required a very wide shallow container, preferably on a turntable and a very particular pencil. In some respects, this iteration was an improvement, as now the experiment could be ‘performed’ for an audience.

except in Jackson’s version ink isn’t used, the water is clear and: “At every successive fall of the water, he [Burr] traced lines on the model, indicating the curves shown upon its surface by the successive lowering of the water.” I tried recreating this version too, but ‘tracing’ with a sharp point tended to nudge the model, and ink (and charcoal and graphite) smudged in the water. To draw a steady clean line required a very wide shallow container, preferably on a turntable and a very particular pencil. In some respects, this iteration was an improvement, as now the experiment could be ‘performed’ for an audience. Until I started my own versions of these experiments, I hadn’t realised the implications of the different techniques: ‘flooding events’ versus ‘traced lines’; that the latter lends a more ‘abstract’ diagram-like appearance to the model, this version of the experiment is the one advanced by Alfred Wilks Drayson in the 1860s.

Until I started my own versions of these experiments, I hadn’t realised the implications of the different techniques: ‘flooding events’ versus ‘traced lines’; that the latter lends a more ‘abstract’ diagram-like appearance to the model, this version of the experiment is the one advanced by Alfred Wilks Drayson in the 1860s.